Through the progression of BCM288 [Transnational Media & Cultural Industries] I have been challenged to explore both Australian and international industries that contribute to the audience experience, production and content therefore creating a global media and culture. Each week introduced a new topic along with case studies that assisted me in grasping the transnational development of information and underlying values and dimensions that came with them.

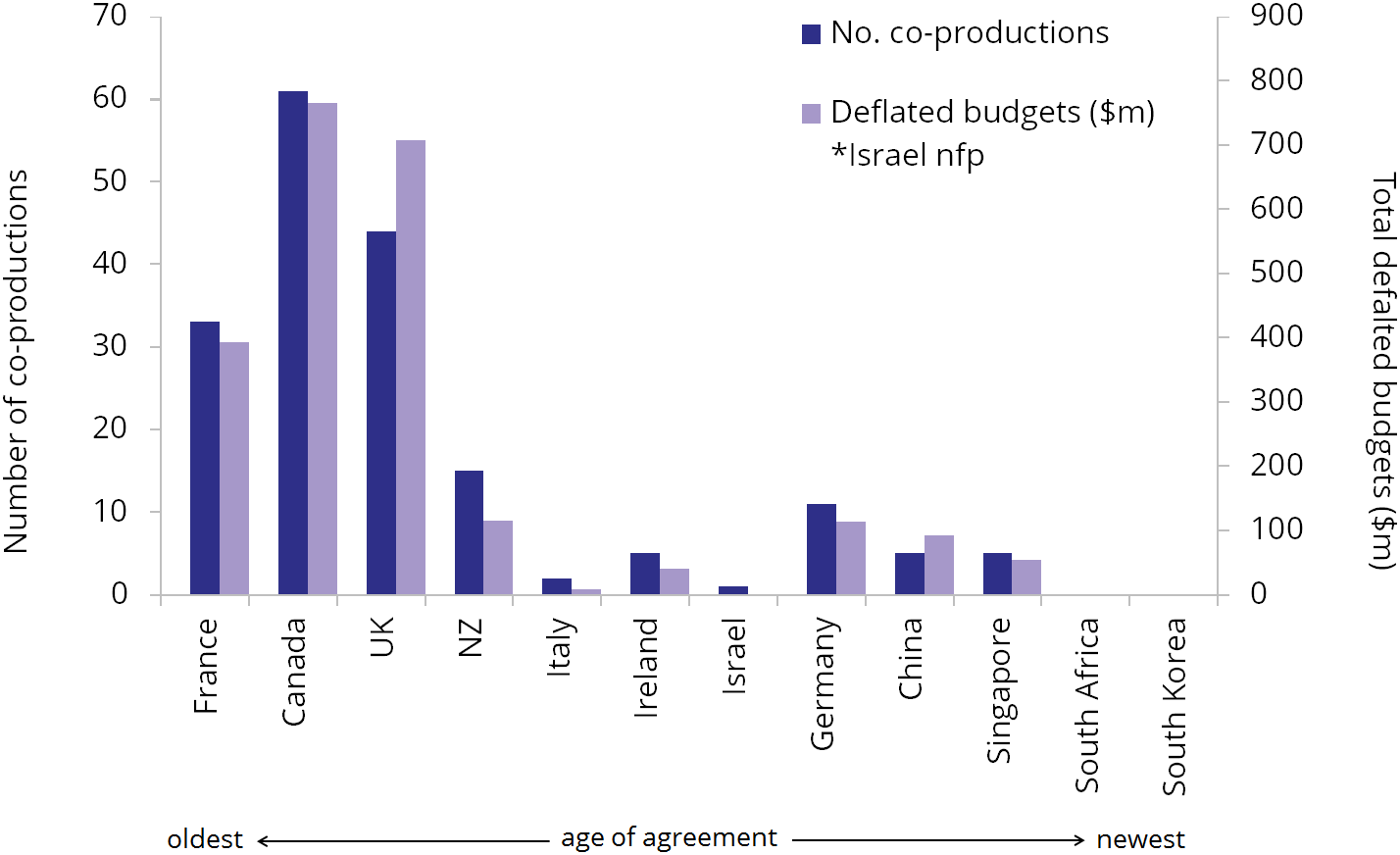

At the beginning of this subject I had little knowledge about television and film, only their end results in the box office. BCM288 allowed me to delve into the development of such projects through notions such as ‘Co-Productions’ and the localisation of television within different nations. Firstly, I was able to compare elements such as the financial funds that differed between domestic produced films and that of co-produced whereby some of the numbers were staggering. The immense difference therefore impacted the kind of project that was being developed and then shared with global audiences.

We explored the context of television within Australia whether it be the production, exhibition, reception and potential transnational success of programs. The use of ‘Black Comedy’ was evident where we researched it’s adaptation, cross -culture potential and its offensive/satirical label that was thrown by audiences and critics. This then led to my individual exploration into the depiction of multicultural societies and cultures in the the Australian television industry. The notions of ‘Aboriginalism’ and the ‘Indigenous Public Sphere’ stuck with me, where this form of representation leads to discourses that create expectations and assumptions of Aboriginals on the television screen; outlining one’s overall presence portrayed by attire, personality, sound and depicted values. This research dealt with the issues of stigmatization, tokenism and stereotyping humor that was prevalent in an industry that has previously lacked has the contribution of the affected minority. The ways that diverse forms of Indigeneity have been convoluted in the Australian television industry have altered perceptions nationwide and perhaps globally. These representations within the screen have been inhibited by the ideas of ideological disparities and are now slowly moving towards the empowerment of vulnerable issues and populations.

Cosmopolitanism was also a notion that I found myself engrossed in. Cosmopolitanism is the ideology that all human beings belong to a single community, based on a shared morality. Through a class debate, our group was to argue against the statement ‘Does unprecedented rise in global media flows and human mobility always lead to cosmopolitanisation of culture and political values?’ I found this task very challenging though we were able to explore key concepts such ‘Ethnocentrism’ which is the evaluation of other cultures according to preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of one’s own culture. How can you one expect shared morality and values of a nation with diverse communities from broadcasted parochial content, especially that of a country that oppresses its inner populations.

This subject has given me a wider perspective upon global media as a whole rather than that closed off by borders. I was able to learn about global media flows, their impacts and the logistics of how they become what they are and what they mean to stakeholders both active and passive. It has built upon my skills to research specific components of the media market and help bring them to the limelight for myself and those who follow my blog spot.